Political Theory as Activism: A Case Study in Higher Education’s Decay

AMERICAN CAVE: A series analyzing America's salient political and cultural trends.

Political Theory is undergoing a unique fate at the moment higher education excises the social sciences and humanities (anything non-STEM) from their curricula. Studying politics has now given way entirely to the desire to transform it. For those trained or working as Political Theorists, changes within this discipline are especially urgent; but these changes also reveal broader trends in how the next generation, particularly the elite, will be educated.

Political Theory As Ideology

Political Theory falls under the auspices of both disciplinary categorizations mentioned above. When Political Theory is recognized as a part of political science, then it is a social science. When it is called by its other (generally preferable) moniker, Political Philosophy, it is undertaken by philosophy professors and students, then it falls under the banner of Humanities. The terms are often used interchangeably and these academic distinctions are of little importance, save for one issue: “theorizing” about politics shares more with ideology than with philosophy. Philosophizing about politics began with Socrates, and the founders of all forms of political studies were his students, Plato, Xenophon, and Aristotle. Political Theory today, however, is no longer concerned with knowledge and truth about political phenomena, but instead dedicated to propagating certain “ideologies.”

Philosophizing about politics means investigating all assumptions about it, including especially human nature and the place of culture and laws (nomos in the Greek). “Ideology” is used today, though, synonymously with belief, assertion, worldview, which is to say one’s opinion about politics. The derogatory tone heard in the term “ideologue,” someone with a fixed, rigid ideology, betrays a distinction. Ideologues are not open to reconsidering their views; they are not philosophizing, but preach or proselytize or recruit. An ideology is a firmly-held and committed position on what the problems in the world are, and even more importantly, on what needs to be done (oftentimes aside from what would seem manifestly necessary). But worse, ideology is often simply one’s wish for how the world ought be; it becomes an imposition of will, ignoring questions of the possible and desirable. Ideology’s fruit is political activism.

Contrasting with ideology is wisdom. Recall that philosophy in Greek means “love of wisdom.” It is not possession of wisdom or perfect knowledge or enlightenment or divine revelation. And it is most certainly not “wokeness” (a term clinging to shaky Enlightenment ideals). It is a pursuit, if an imperfect pursuit, where one’s recognition of insufficiency is as integral to the pursuit as the desire for truth itself. To stop and suddenly say “I am now officially wise!” is to betray what philosophy, at least as originally conceived, meant. Various methodological approaches to the history of philosophy, along with other related disciplines, often reduce the rich complexities of philosophic questions, of what wisdom might be, to “-isms,” missing philosophy’s original purpose.

An activist Political Theory simply voicing contemporary partisan grievances will bury further into the distant past a tradition of open inquiry, truly diverse debate, and even some fundamental truths about principles of justice which guide our shared political life.

Wisdom, politically speaking, is prudence or practical wisdom. Decisions of course must be made, actions taken, policies formulated, and thus philosophizing about politics does not furnish solutions. This is to recognize an important political truth the ideologue does not: solutions to problems, like treatment of illness, invariably give rise to side effects or unintended consequences. Doctors are now faced with drug-resistant bacteria and viruses that have adapted to scientific advances. This does not render these advances irrelevant; but it means we must continue to refine possible solutions to new problems. Similarly in politics: claims that “if we just do X, problem Y will be solved evermore” are illusory, and even dangerous. We hear all the time today from activist ideologies with purportedly coherent solutions or totalizing plans. But even clear-headed proposals to political problems suffer side effects. Prudence is weighing a best possible outcome against the costs that necessity extracts.

Is this education to political prudence and even wisdom to be found in academia today? Is this not what “Political Theory” was originally intended to do? If not, then what is it intended to do?

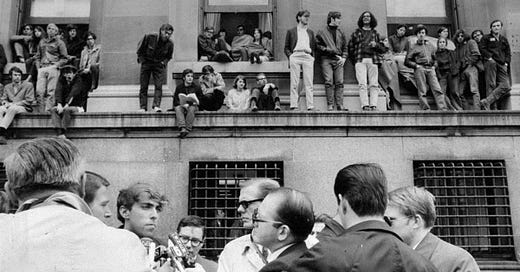

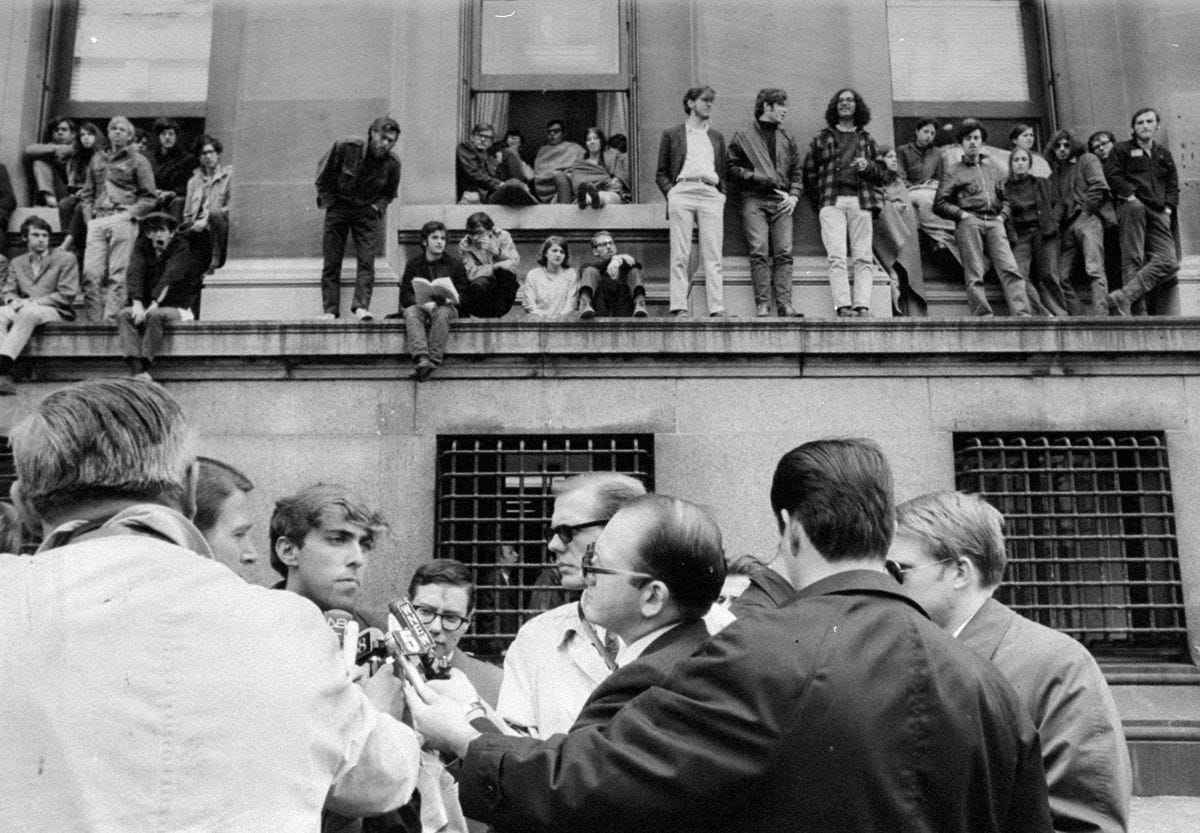

Where It Began

Revolution in the universities boiled over in the 1960s. But tradition was allowed to remain for a time. Corners of the traditional academy were still allowed to exist. Even as post-modernism slowly overtook the humanities and social sciences, the canon was still not thrown out entirely (a canon, it should be noted, far from unanimous on a whole host of questions. Marxist academics in the first half of the 20th century still knew their Aristotle). Within Political Science, other subfields, such as the old timers in International Relations, were qualitative and used history and could talk war with Political Theorists. They shared an affinity even if questions and “methodologies” differed. Students could weigh which arguments were most persuasive.

But a movement away from “values” (the moral questions Political Theory certainly treats) not only as unscientific but in line with the post-modernist assertion that they did not even exist, opened the door for an entirely “scientific” (i.e. quantitative) Political Science which ironically shared the throne with a rising post-modernist Political Theory.

One is amazed at how easily this has been accepted.

Then again, two factors aided its assent: The radical political left saw the utility in demonizing their opponents, while post-modernist language with its accusations of colonialism, racism, and other “I’m blaming you for this” -isms, became a perfect Political Theory to legitimize a tribal “us vs. them” dynamic, a dynamic the U.S. Constitution expressly aimed to mitigate. And the guardians of the academy sat by and allowed their tradition to be swept away. Mortimer Alder, Allan Bloom, and others protested. But their heirs only seemed to muster a defense aimed at keeping a seat at the table. Not enough was done to stop the takeover because the humanities and social science folks themselves suffered from a guilty conscience – they could not defend against the revolutionaries’ attacks what they themselves claimed was valuable, at least not well enough to convince anyone to keep reading Plato or Shakespeare.

Now our activist academy, merely reflecting back what it started and what’s happening in America at large, argues tradition cannot even exist alongside post-modernism, as the latter morphs and sharpens into various grievance studies. Said tradition is obviously far too “-ist” or “-ic” (insert your preferred suffix). Activism is rejection of tradition (based on presumptions never tested) coupled with specific agenda items and policy goals one must be blindly dedicated to achieving. It becomes openly guided, not by traditional questions, or even by any questions at all, but by achieving effects which presuppose answers to those questions. This is the issue. No longer do we ask “What is justice?” as Socrates did. Instead, we must actively work for “social justice.” That social justice raises a whole host of problematic claims and is itself woefully ill-defined, wallowing in abstraction and jargon, is ignored without further ado.

Political Theory Today

Replacement of Political Theory by a counterfeit is worse than any death due its allegedly unscientific uselessness (its previous threat with the early 20th century rise of quantitative “social science”). For a replacement Political Theory allows an appeal to a noble and illustrious tradition legitimizing an impostor – ideological activism. Whether academic activists admit it or not, they enjoy resting their activities on the broad shoulders of the traditional canon to lend legitimacy to their new dogma. Classical works, when studied at all, are twisted in service of this new dogma: Greek poets interpreted via postmodernism purportedly assuring us that moral relativism has existed all along.

Yet if there is one lesson from the Political Theorists of the past deserving our attention today it is surely this: Any political or ideological claim is necessarily rooted in justice, in a view about how country, citizens, and government should be arranged, to say nothing of implicit claims regarding human nature itself. In abandoning a non-ideological, non-activist Political Philosophy, we have abandoned investigation of what justice is and the side effects that accompany even the best laid plans (which is to say, the very difficult question of the possible limits to perfect justice, among many related inquiries). Perhaps not surprisingly, our lack of seriousness in learning about justice is coupled with absurdly staunch claims about what justice (“social justice”) is. Add in the fact that post-modern political theorizing, the root of today’s ideologies, denies there is any such thing as justice (and truth) and one reaches the inevitable conclusion that all politics is merely an unmitigated exercise of power.

Erasing the politically pernicious effects of an activist post-modernism is the task today. But this task cannot get underway from within an academy that seeks to further politicize its so-called research, while also banishing from students the foundational knowledge that, like it or not, has informed our contemporary political situation. A professional association’s flagship journal that selects its entire 12 member board based on sex; political litmus tests through diversity statements and protocols; and new hirings in Political Theory that expressly demand activist engagement in on-going political disputes of assumed importance, all furnish evidence of an academic discipline bowing to a new orthodoxy. An activist Political Theory simply voicing contemporary partisan grievances will bury further into the distant past a tradition of open inquiry, truly diverse debate, and even some fundamental truths about principles of justice which guide our shared political life.